Ezra gave this speech at the July 1963 meeting of the American Library Association in Chicago, where the Caldecott Medal for “the most distinguished American picture book for children” was awarded for The Snowy Day. The text and illustrations were published in The Horn Book Magazine (August 1963).

I am very happy to be here to receive this great honor for a book which means so much to me, a book which led me into new avenues of expression.

I would like to tell you how The Snowy Day was done, and how I arrived at the technique used in it. However, it would be more accurate to say that I found myself participating in the evolvement of the book.

First let me tell you about its beginnings. Years ago, long before I ever thought of doing children’s books, while looking through a magazine I came upon four candid photos of a little boy about three or four years old. His expressive face, his body attitudes, the very way he wore his clothes, totally captivated me. I clipped the strip of photos and stuck it on my studio wall, where it stayed for quite a while, and then it was put away.

As the years went by, these pictures would find their way back to my walls, offering me fresh pleasure at each encounter.

In more recent years, while illustrating children’s books, the desire to do my own story about this little boy began to germinate. Up he went again—this time above my drawing table. He was my model and inspiration. Finally I began work on

The Snowy Day. When the book was finished and on the presses, I told [author] Annis Duff, whose guidance and empathy have been immeasurable, about my long association with this little boy. How many years was it? I went over to Life magazine and had it checked. To my astonishment they informed me that I had found him twenty-two years ago!

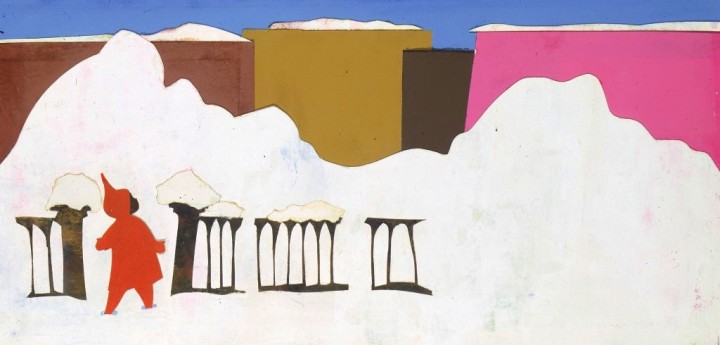

Now for the technique—I had no idea as to how the book would be illustrated, except that I wanted to add a few bits of patterned paper to supplement the painting.

As work progressed, one swatch of material suggested another, and before I realized it, each page was being handled in a style I had never worked in before. A rather strange sequence of events came into play. I worked—and waited. Then quite unexpectedly I would come across just the appropriate material for the page I was working on.

For instance, one day I visited my art supply shop looking for a sheet of off-white paper to use for the bed linen for the opening pages. Before I could make my request, the clerk said, “We just received some wonderful Belgian canvas. I think you’ll like to see it.” I hadn’t painted on canvas for years, but there he was displaying a huge roll of canvas. It had just the right color and texture for the linen. I bought a narrow strip, leaving a puzzled wondering what strange shape of picture I planned to paint.

The creative efforts of people from many lands contributed to the materials in the book. Some of the papers used for the collage came from Japan, some from Italy, some from Sweden, many from our own country.

The mother’s dress is made of the kind of oilcloth used for lining cupboards. I made a big sheet of snow-texture by rolling white paint over wet inks on paper and achieved the effect of snow flakes by cutting patterns out of gum erasers, dipping them into paint, and then stamping them onto the pages. The gray background for the pages where Peter goes to sleep was made by spattering India ink with a toothbrush.

Friends would enthusiastically discuss the things they did as children in the snow, others would suggest nuances of plot, or a change of a word. All of us wanted so much to see little Peter march through these pages, experiencing, in the purity and innocence of childhood, the joys of a first snow.

I can honestly say that Peter came into being because we wanted him; and I hope that, as the Scriptures say, ”a little child shall lead them,” and that he will show in his own way the wisdom of a pure heart.